Snapchat, as with all social media platforms, has a unique set of norms which are informed primarily by the collective values of the participatory community and how said community interacts with the platform based on the platform’s affordances. These norms are reinforced over time and evolve continually to reflect changes in the nature of its userbase. Perhaps the most overt distinction between Snapchat and other popular social media platforms is the absence of permanence. Whereas media posted on platforms such as Facebook and Instagram remains accessible for long periods of time, often perpetually, Snapchat is designed in such a way that constrains sharing between users to rapid, short lived and ‘in the moment’ communications. This constraint contributes largely to the formation of Snapchat’s norms i.e. the nature of content users would expect to send and receive over the platform and the content users would deem as inappropriate.

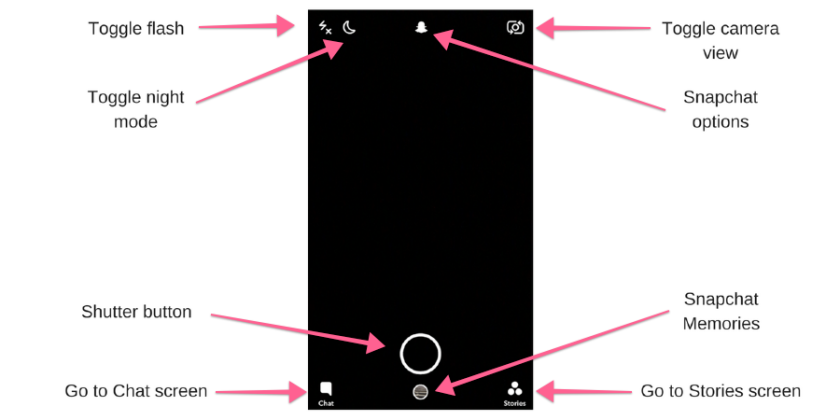

Snapchat is a mobile based social media platform which was originally launched in September, 2011 (Colao, par.8). It allows users to send and receive both photos and videos, these media are referred to as ‘snaps’. Photo snaps can be set to disappear from one to ten seconds after being opened, or until they are closed by the recipient. Video snaps are also constrained to ten seconds in length but can be sent as a ‘multi-snap’ which is a succession of up to six snaps recorded concurrently. The length of the snap is at the discretion of the sender who utilises the timer icon, which is found on the camera screen, to alter this setting.

The ‘Camera Screen’ of Snapchat which is the default screen of the app.

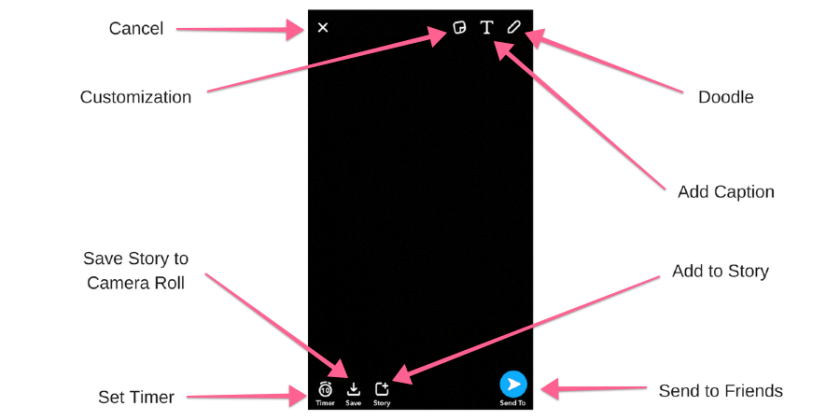

The ‘Edit Screen’ of Snapchat which appears once the Snap has been captured.

Snapchat is used as a mode of ‘pictorial conversation’, an increasingly common format of communication in a world dominated by the ubiquitous ‘smart phone’ (Villi p.42). Such communication has taken the place of postcard sending, in which images are integral to the communication but not necessarily the referent object of the communication. Unlike postcards however, snaps establish a connection between the message and the ‘real-time’ context. Given that smartphones are highly portable, it is not uncommon for users to take their devices into areas not traditionally regarded as suitable venues of communication. For example, people will often bring their phones with them into bathrooms when using a toilet or preparing for a shower and continue using their device to communicate up until it is no longer possible for them to operate their device. Such an act would have been considered reprehensible prior to the advent of mobile smartphone technology, yet as we have further adapted as a society to mobile phone attachment, there has been an observable shift in norms. A 2013 article published by The Daily Edge titled “Nine dodgy Snapchats everyone sends but probably shouldn’t” identifies “the toilet snapchat” as a common type of snap shared between friends. While Facebook, Twitter or Instagram users would not be expected to share such vulgar and personal photographic insights publicly or even over a private messenger, Snapchat apparently establishes itself as an appropriate host for communication of this nature. The reason for this differentiation comes down to the fact that Snapchat does not afford for the permanent hosting of images and thus users have confidence that any media shared person to person will not survive beyond the context and time in which it is sent and received. Because of this it is considered a norm of Snapchat that informal and unflattering images are shared regularly between users whereas images hosted on the aforementioned platforms tend to present a much more tailored and refined self.

The ‘Toilet Snapchat’ is an overt example of over-sharing.

Snapchat’s time limited photo/video messages afford the ideal platform for the sharing of intimate and explicit imagery. Despite the platform’s perceived convenience for this nature of communication, sharing content of such a personal nature over Snapchat does not come without significant risk. Should the recipient of a snap decide they want to retain the image beyond the established time limit, they may circumvent the images self-deletion by capturing a screenshot on their device, usually performed by the pressing of two buttons on the device whilst holding one finger on the screen so as to keep the message open. Snapchat does not prevent users from capturing screenshots although it does notify the sender in the case of the recipient screenshotting their message. In this aspect, Snapchat affords a means of social surveillance, whereby users can monitor the behaviour of the users they interact with and keep track of any norm-breaking activities (Marwick p.1). The norm-breaking activity in this instance being the permanent retention of media which was intended to be shared for only a few seconds by means of screenshotting. These interactions between users and the architecture of Snapchat contribute to establishing a cultural field within which the norms arise, acting as unspoken rules which regulate acceptable standards of behaviour (Danaher et. Al. p.22). When these rules are transgressed, the culprit’s reputation, and subsequently their social capital, is damaged. This reprimand plays a pivotal role in the function of social capital to maintain social order. An Icelandic study into the role of sexting within Snapchat found that respondents most commonly perceived users who collect private snaps as being immature, mean, sad, obsessed and disrespectful (Guðmundsdóttir p.44).

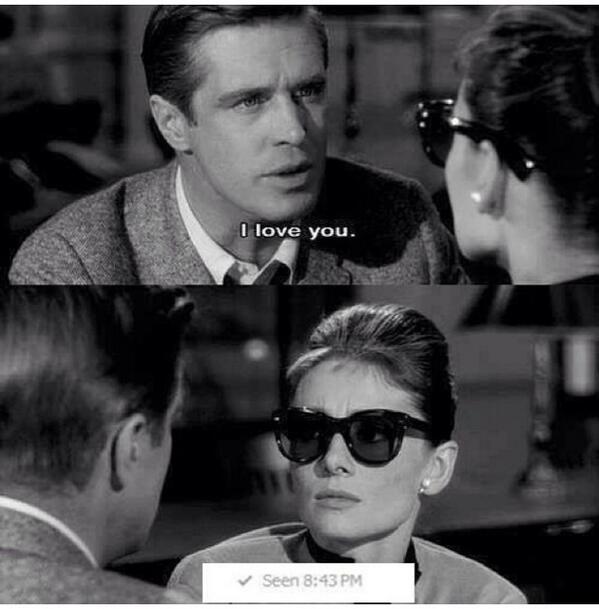

Another aspect of Snapchats architecture that affords a means of social surveillance is that it informs senders of the status of the snaps that they have sent. The three steps a snap travels through from being sent to being received are: “Sent”, this means your snap has been sent away to the ‘cloud’ of Snapchat but has yet to arrive to the recipients device, “Received”, your snap has entered the recipients inbox but they have yet to open it, and “Opened”, the recipient has viewed your snap. Seen in similar manifestations across other platforms such as the “Seen” feature of Facebook’s Messenger app, this information enforces the norm of reciprocated communication. Without such a feature, users would be able to selectively respond to and ignore communications via Snapchat without detection, if this were the case it would be easier for users to be less engaged on Snapchat as there would be no social pressure to establish and enforce the above-mentioned norm. It is in the interest of Snapchat to maximise the engagement of its users and so in establishing this norm (through implementation of the “Opened” feature) it is able to trade off the discretion of its users for an increase in pressure to respond to snaps. Whether or not a recipient has a genuine reason for not being able to send an immediate response, the silence of the recipient implies the message that they are intentionally ignoring the sender. Pre Web 2.0 modes of communication such as post and early text messaging afforded discretion in this sense, whereby senders had no real way of knowing whether or not their messages had been read or even received and thus ignoring communications was more commonplace. As our abilities to conduct social surveillance on the people we communicate with increases, the norms of communication are shifting to a point at which friendly and casual communication, due to the unspoken pressures assigned to response, becomes increasingly invasive.

Sometimes silence says more than words ever could.

“(Snapchat) has been built to hide information from unintended audiences in exactly the reverse of Facebook’s super-public system”, this explains why Snapchat users feel less apprehensive broadcasting more private and less flattering snapshots into their lives than users of other platforms (Prado 91). Due to the increased willingness of users to send private media, the consequences of context collapse are significantly higher (Marwick, The Public Domain: Social Surveillance in Everyday Life 1). A commonly overlooked risk associated with Snapchat is the accidental sending of snaps to unintended recipients. Because of the fast pace of sending and receiving Snapchats and the layout of the “Send to…” screen, it is very easy to select the wrong contact and click the ‘send’ arrow before realising the error, once the snap has been sent there is no possible way for the sender to intercept the snap. This is no great error when the accidental snap is of an innocuous nature but in instances of accidentally sending explicit snaps, or ‘nudes’, to unintended contacts, including but not limited to: friends, co-workers and family, the social consequences can be extreme and pose serious real-life ramifications. An example of such ramifications was demonstrated when in Florida in 2016 a young woman commited suicide after the nude Snapchats of her were leaked throughout her school (Klausner 1).

Snapchat as a social media platform affords many new possibilities for social interaction through its unique affordances which have adapted a cultural field within which there is great emphasis on hyper-personal sharing (or over-sharing) and unprecedentedly rapid, real-time communication. These affordances encourage Snapchat users to be increasingly engaged with each other and thusly the platform and contribute to the growing culture of our attachment to social media outlets. New norms have been established which reflect the Snapchat community’s values of instantaneous exchange of media and immediate response which subsequently intensify the social pressures involved with Web 2.0 interaction. While Snapchat allows for highly personalised communication, it also presents new and significant dangers which are amplified by the community’s apparent willingness to post unfiltered and oftentimes highly private media. Certain norms exist to encourage users to respect one another’s privacy i.e. the discouragement of screenshotting and distributing said screenshots without permission, these norms are crucial as at this point in time little is done by law enforcement to protect the privacy of users globally. Finally, as we become further inclined to recklessly overshare and further distanced from traditional norms of privacy it has never been more paramount for the Web 2.0 community to become conscious of the potential consequences of the very behaviours which Snapchat breeds and thrives off.

WORKS CITED

Colao, J.J. “Snapchat: The Biggest No-Revenue Mobile App Since Instagram.” Forbes. 27 Nov. 2012. Web. 24 September 2017.

Guðmundsdóttir, Andrea. Sexting, Snapchat & Social Norms:

Because everybody is doing it? MA thesis. Erasmus University Rotterdam, 2015. Web. 26 September 2017.

Klausner, Alexandra. “Nude Snapchat blamed for teen’s suicide.” New York Post. NYP Holdings, Inc., Jun. 2016. Web. 28 September 2017.

Leitch, Alex. “Exclusive Space.” Social Media and Your Brain: Web-Based Communication is Changing How We Think and Express Ourselves. California: ABC-CLIO, LLC, 2017. 91-92. Google Books. Web. 27 September 2017.

Loftus, Valerie. “9 Dodgy Snapchats That Everyone Sends, But Probably Shouldn’t.” The Daily Edge. Journal Media Ltd, Aug. 2015. Web. 25 September 2017.

Marwick, Alice E. Status Update: Celebrity, Publicity, and Branding in the Social Media Age. Connecticut: Yale University Press, 2013. Jstor. Web. 24 September 2017.

Marwick, Alice E. “The Public Domain: Social Surveillance in Everyday Life.” Surveillance and Society 9.4 (2012): 378-393. ProQuest. Web. 28 September 2017.

Villi, Mikko. “Visual Chitchat: The Use of Camera Phones in Visual Interpersonal Communication.” Interactions: Studies in Communication and Culture 3.1. (2012): 39-54. University of Helsinki Research Portal. Web. 26 September 2017.

Webb, Jen, Tony Schirato and Geoff Danaher. “Cultural field and the Habitus.” Understanding Bourdieu. (2002): 21-44. SAGE Knowledge. Web. 25 September 2017.

Image Credit

Annotated Snapchat screens both from: “How to Start Posting Snaps on Snapchat app for Iphone” http://www.iphonehacks.com/2016/12/how-to-start-posting-snaps-snapchat-iphone.html

Toilet Selfie from: “9 Dodgy Snapchats that everybody sends, but probably shouldn’t” http://www.dailyedge.ie/snapchats-everyones-guilty-of-sending-2256049-Aug2015/

‘Seen’ meme from: Life Looks Better in Black blog https://lifelooksbetterinblack.com/2014/07/